The above is a beautiful painting by William Holman Hunt of his wife Fanny. Take a close look at the pattern on her shawl, does it ring a bell? Most of you must have concluded that it is Paisley. And you’re right. But here comes the actual question, how many of you know that the original name of this motif is boteh or buta?The East India Company imported large quantities of paisley shawls from Kashmir and Persia to Europe in the 18th and 19th Centuries, and the exotic pattern became a sensation on the continent. The shawls were soon imitated and mass-produced throughout Europe, notably in Wales and the town of Paisley in Renfrewshire, Scotland. Over time, the original names of the motif ‘boteh/buta’ disappeared and the English term ‘paisley’ emerged. Today paisley is often labelled as ‘boho,’or ‘vintage’ without crediting its South Asian and Persian roots. Racism allowed the West to strip cultural meaning, rename it, and sell it back as fashion.

As mentioned by Anita Desai, “People in more privileged positions often take elements from less fortunate cultures and use them in their own work without giving credit where credit is due. This practice is called cultural appropriation.” If Western suits were suddenly rebranded as ‘ancient Indian formalwear,’ that is cultural appropriation. It sounds absurd. Yet this is exactly what happens when Western industries strip elements from non-Western cultures, repackage them, and profit without respect or recognition.

And why is this problematic? Why is it very easy to copy and very difficult to give credit to the people or cultures behind an art? Racism—especially in the form of cultural hierarchy, systemic bias, and colonial legacy, is an underlying reason for why Indian and other non-western crafts are so often appropriated, erased, or undervalued while being celebrated when rebranded in the West. For instance, when an Indian craft is presented by Indian artisans, it may be labeled as ‘ethnic,’ ‘cheap,’ or ‘local.’ But when a European designer uses the same design, it’s considered ‘timeless,’ ‘luxury’ or ‘art.’ It is the year 2025, and cultural appropriation is still making headlines, louder than ever.

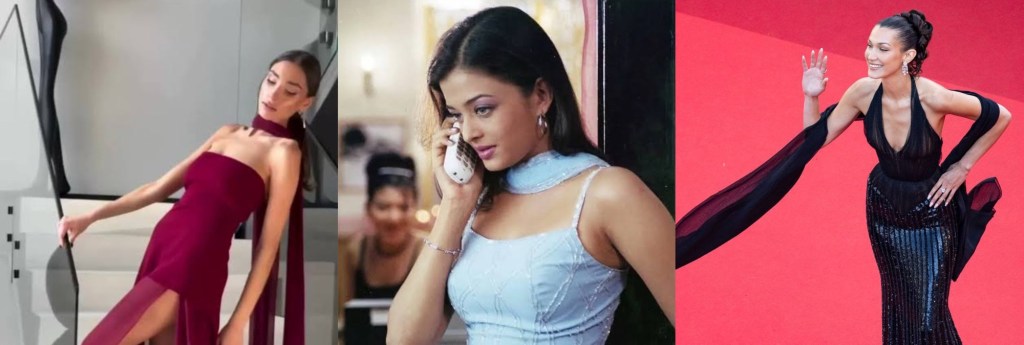

Guess what the long flowy garment in the above pictures is called? If you say Dupatta, at least some may disagree, because the Indian Dupatta now has a whitewashed name on social media, ‘the Scandinavian scarf.’ The dupatta is an integral part of many Indian outfits and is more than a piece of fabric—it’s a symbol of cultural identity, modesty, femininity, and tradition in South Asia. But when the roots of dupattas were erased and rebranded for the Western audience by giving it a European origin and showcasing them on white bodies, the exotic dupattas suddenly became elegant. This is a clear case of the effect of cultural hierarchy, the belief that some cultures are more refined, superior, or beautiful than others. When brown Indian women are mocked and stereotyped as ‘traditional,’ ‘oppressive,’ or ‘local’ when they wear a dupatta, and white women remain ‘modern’ and ‘elegant’ even if they style the very same dupatta, it highlights the prevailing superiority of Western culture. Only if the West, replicate the so-called ‘local’ designs, will they be considered superior. This disparity reveals a deep-seated bias that needs to be addressed.

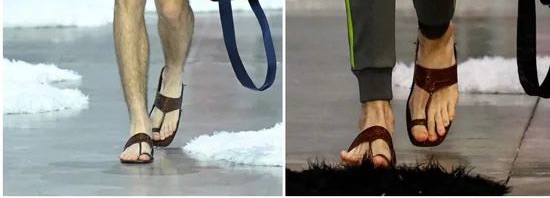

Kolhapur has a rich legacy of skilled artisans who have been crafting the exquisite Kolhapuri sandals for generations. In the above images, you can see the footwear that the Italian luxury fashion house Prada had launched during an international fashion event held in Milan. But there is a twist, the footwear which has a striking resemblance to Kolhapuri sandals is named “Toe Ring Sandals.” Yes, they are rebranded under the European label without acknowledging their true origins. On top of that, these sandals are priced over ₹1 lakh per pair. This incident showcases systemic bias, which refers to unfair treatment or discrimination that is built into the policies, structures, or practices. It often benefits dominant or majority groups while disadvantaging minorities or marginalised people. When Prada reaps profits by repackaging the traditional Indian craftsmanship for the global market, the original artisans remain underpaid and excluded from recognition.

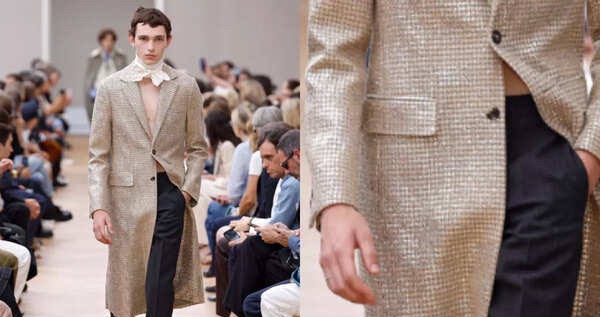

Just when the buzz around Prada’s Kolhapuri chappal controversy began to quiet down, another luxury fashion house stepped into the spotlight, drawing inspiration from India’s vibrant heritage without nod of acknowledgment. Dior presented a stunning gold and ivory coat with a sharp houndstooth twist priced at INR₹1.67 crore. The spectacular embroidery on the coat wasn’t extravagant European craftsmanship; it was made using Mukhaish, a dying art of traditional Indian embroidery technique from Lucknow, known for its intricate metalwork and 12 artisans worked for over a month to finish one coat. Yet, there was no acknowledgement of the roots of the craft and zero credit to the skilled Indian artisans who made it possible. What makes this worse is that it came barely days after the Kolhapuri controversy. This is a lasting impact of colonial legacy—colonies were structured around extracting wealth using forced or cheap labor from racially “inferior” groups. And even today, former colonies are treated unequally in international systems.

Yes, we live in a globalised world and cultures being fluid, do influence each other. But when dominant cultures steal from marginalized ones without context, it’s exploitation, not fair exchange. When Western designers profit from indigenous patterns, the communities who deserve recognition remain impoverished.

Fashion can be a vehicle for positive cultural dialogue and exchange, celebrating the richness of cultural diversity. According Anita Duggal, “When done thoughtfully, cultural exchange in fashion can foster inclusivity, highlight the richness of various traditions, and empower communities.” What is the solution? Rather than stealing ideas, designers can collaborate with artisans from marginalized cultures or pay homage to traditional craftsmanship. This can create meaningful connections that elevate and honor the original cultural contexts.

Colonial powers did not just invade lands, they built their wealth by extracting resources, labour and culture from those who they considered inferior. Today imperial nations are not invading lands, but if they continue to uphold the myth of European superiority, justifying the theft of cultural heritage, it is repeating history in disguise.

To wrap up my article, I want to share a powerful quote that has stayed with me since my college years:

“Colonialism is not satisfied merely with holding a people in its grip and emptying the native’s brain of all form and content. By a kind of perverted logic, it turns to the past of the oppressed people, and distorts, disfigures, and destroys it.”

-Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth

Scandinavian scarf? Such a long way away from the humble dupatta. And I say nonsense to renaming it and everything else.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exactly! Why erase the beauty of what it truly is?

LikeLiked by 1 person